One of the common marketing messages behind alternative medicine is that is represents true innovation in healthcare. Using one Prince Charles’ favourite words, it tries to offer “integrative” services by combining the best of ‘Western’, or orthodox, medicine with ancient traditions, Eastern practices and New Age ways of knowing.

One of the common marketing messages behind alternative medicine is that is represents true innovation in healthcare. Using one Prince Charles’ favourite words, it tries to offer “integrative” services by combining the best of ‘Western’, or orthodox, medicine with ancient traditions, Eastern practices and New Age ways of knowing.

Doctors, in this thinking, are portrayed as hamstrung by their conventional medical training or, even worse, beholden to their imagined paymasters in Big Pharma. Doctors either cannot conceive that there are medical ‘paradigms’ outside of their University experience, or can do, but fear their paychecks will run out if their depart from their lizard master orders to keep dishing out the pills.

The Saatchi Bill, currently passing through the Houses of Parliament, flirts with these ideas. Its premise is that there is a pool of treatments waiting to brought into mainstream practice by conventional doctors who want to innovate. But stopping them is a fear that they will be subject to punitive litigation for departing from the safe and orthodox path.

Opponents of the Bill point out that there is absolutly no evidence that doctors are afraid of genuinely innovating because of inadequacies in the law. Of course, there is a very big difference bewteen fear of litigation because you have been negligent in providing quack treatments and fear of litigation becaue you have wanting to genuinely innovate and advance medical knowledge. Whilst it is clear that many doctors are sued because of claims they were negligent, there is no evidence that any doctor has been sued because they tried to innovate.

But at the heart of this debate then is what we mean by the words ‘medical innovation’. To one person, a treatment might be innovative; to another, straightforward quackery.

The Saatchi Bill has not tried to define medical innovation despite it being the subject of the texts. One of the fiercest opponents of the Bill, Lord Winston, has tabled ammendment to try to make such a definition. I must admit, I do not understand why these definitions have been put forward as they do not appear to answer the questions I have posed here.

Let’s see the proposed changes,

For the purposes of this Act, an “innovation” means—

(a) any medical treatment, the results of which have not been reported

in peer-reviewed medical publications or have not been subject to

the scrutiny of a published clinical trial;(b) the use of any drug, vaccine or pharmaceutical agent which has not

undergone appropriate clinical trials required by UK or EU

legislation;(c) the use of any drug, vaccine or pharmaceutical agent for a purpose

other than that stipulated by the manufacturer;(d) the insertion or application of a device or instrument for which

approval has not been given by the relevant EU regulatory

authority; or(e) the application of a monitoring device or biosensor for which

approval has not yet been sought or given.”

The problem I see with the above definitions is that just about every quack claim out there could fit the description of ‘innovative’? How many papers out there are there showing that homeopathy cannot treat brain tumours? What is to stop a doctor using homeopathy to treat cancer here? There are no trials to support such a treatment. So should we consider homeopathic treatment of cancer innovative or negligent quackery?

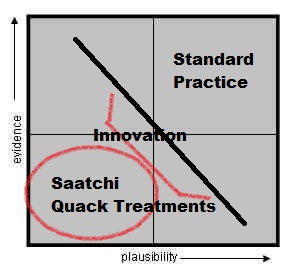

Merely conidering the availability of trial data is not sufficient to rule out negligent treatments. The treatment has to have a rationale behind it: it has to be supportable by plausible medical and scientific arguments. A few years ago, I wrote about how it was wrong for supporters of Evidence Based Medicine, such as the Cochrane Collaboration, to call for more research into treatments that were implausible, such as homeopathy. I introduced a visualisation of how to think about whether a treatment was scientific in its rationale or was quackery. A treatment could be plotted on a chart with two axis: one, the degree of evidence available for the treatment; and two, the level of plausibility behind the treatment. We could then segment treatments according to the quadrant on the plot they fell into.

Scientific medicine lies towards the upper right quadrant. Quackery in the lower left.

Accepted medical treatments ought to have an appropriate level of evidence to overcome any doubts regarding their plausibility. Extrordinary claims ought to have lots of evidence. Unambiguouss treatments, where outcomes are binary and unquestionable, probably need a lower level of evidence.

So, innovative treatments are those that exist below this threshold but are not implausible. Quackery will fill the gaps below this line. We can visualise as such:

The Saatchi Bill team claim that doctors are afraid to innovate because they fear litigation if they do so. No evidence of this has been forthcoming. Dominic Nutt, the Bills PR spokesman uses the analogy of a parachute. What patient would not grab the parachute in a crashing plane if there is a sign on it saying ‘not been subject to randomised controlled trials’? It is a daft analogy. Doctor’s are already quite able to offer patients metaphorical parachutes if they exist. Parachutes have not been in RCTS – but their effect are unambigous and their mode of action is well understood and characterised. In our chart above, parachutes would sit in to the bottom right. However, I would challenge you to find many medical treatments that occupy the same space. Medicine is a lot more complicated and ambiguous than this.

Doctors are well able to currently use innovative treatments as long as they are backed by sound medical and scientific reasons as to who they would be in the best interests of patients. Current law protects such doctors and they do not fear litigaiton. Where fears of litigaiton exist is when a doctor would use a treatment that sits towards the lower left quadrant. The Saatchi Bill does nothing for the innovative treatments, but is allowing doctors to act with impunity in the quadrant of quackery. Fear of litigation in this quadrant is a good thing. It is by definition irrational and irresponsible and doctors who use treatments in this area ought to fear the consequences. But to be clear: this is is not fear of innovation, it is fear of negligence.

In this age of patients all having a medical education from the University of Google, the demands on doctors to offer treatments that have been read about online is high. Often this can lead to informed discussions between doctor and patient – which is great – but it can also lead to high expectations, misunderstandings and false hopes. The web is awash with quack cancer claims and planted testimonies to support these claims. As Ben Goldacre has pointed out in his first law of bullshit dynamics ‘there is no imaginable proposition so absurd that you cannot find at least one person, somewhere in the world with a PhD or professional post, who is happy to endorse it’. Managing expectations in this area must indeed be a real challenge. But it is not fear of innovation that is holding doctors back from delving into Saatchi’s quadrant of quackery.

With reference to the first paragraph of the excellent review above:

I am concerned that although the DoH, BMA, Royal Colleges et al use the term ‘integrated’ – they use it in quite a different way from many US institutions, Prince Charles and homeopathic hospitals which have rebadged themselves.

Integrating social, medical, primary, secondary and mental health services is one thing, and to be supported.

Integrating quackery, camistry and nonsense with evidenced based (and recognising the imperfections, I emphasise ‘based’) medicine, is quite another.

Such a use misleads patients, the public and politicians. As Edzard Ernst pointed out, this represents a ‘bait and switch’ attempt to smuggle these notions into the NHS.

I urge all who use the term ‘integrated’ to make it clear in what sense they are using it and what they want to see ‘integrated’.

I have failed to get the BMA to have a clear policy on this point but will press on.

Saatchi is yet another attempt to inflate the quadrant of quackery.

Just what is the problem with these folks?

A perfect conjunction of stupidity and cupidity.

Perfect analysis of the Saatchi bill seeing the ugly flapping webbed feet beneath the serenely sailing duck. The parachute analogy is seriously flawed for all sorts of reasons. If your plane is nose diving then you expectation of life is about 60 seconds from 30,000 ft. The only evidence based solution is indeed a parachute.

If you have terminal cancer your expectation of life is a median of 60 days. Those days can be shortened and ruined by an ignorance based experiment. In fact if the patient put on a parachute and jumped out their window the their expectation of life would be reduced to 60 secs.

I found the parachute analogy deeply disingenuous. It did not come across as an off-the-cuff comment but something they’ve deliberately formulated.

A parachute is self-evidently a good device. It lies on the extreme right-hand edge of Andy’s graph regardless of how far up the vertical axis it may sit.

SCAMsters are at the back of the crashing plane handing out seat-cushions with the word ‘parachute’ written in crayon. Only they can know whether they do this with self-awareness of their actions. Perhaps they might find a cushion that is a bit parachuty, but given the money that’s been invested in SCAM research in the last 30 years, the chances are pretty slim.

All the major SCAM modalities are pretty well busted and the only lacunae of uncertainty probably lie in the realms of herbalism, but the chances of finding any good stuff are much greater when systematic methods of pharmacognosy are applied rather than hoping than some smug middle-class fool in sandals is going to stumble across it.

Indeed it is really quite remarkable just how little room for doubt is now left despite the best and highly biased efforts of NCCAM and its fellow-travellers to find effective SCAM treatments for anything. Which rather shows the Saatchi bill to be a deeply stupid endeavour shot through with the cynical self-aggrandising ambitions of the SCAMsters.

The problem with opposing quackery is that we have too much ‘respect’ for nonsense and those who promote it. We will never be able to appropriately oppose homoeopathy if we do not also oppose Catholicism. We will never be able to appropriately oppose the pH miracle cure if we do not also oppose Allah or any other fictional entity. That is what makes Robert Winston a toothless clown, no matter how well intentioned he almost certainly is.

By opposing some nonsense, and tolerating –even encouraging– other nonsense, we destroy the credibility of those who are attempting to demonstrate that the scientific method is the Better Way.

Life is sometimes simple: one is a cherry picker or one is not. As long as we make exceptions for certain types of belief-based practices, we will never be able to adequately oppose others. Yes, this may antagonise some people in the belief-based camp, but I think it is probably better to antagonise some fiction-based people than to ridicule ourselves by cherry-picking what non-evidence we support and what we do not support. One is evidence-based, or one is not.

Just because the homoeoquack wears a lab coat, does not make his vital force true. Just because the pope wears an expensive white dress does not make his deity true. We must oppose both, for both are promoting nonsense and have not the slightest shred of evidence to support their delusions.

The issue for me is not the faiths as such, whether camist or theist, but the intention of some (Wales, Saatchi, Michael Rawlins (no relation) et al), to have camistry ‘integrated’ with conventional medicine – and to have the tax-payer pay for their whims.

Folks can believe what they like, but should not expect me to pay for their non-evidenced based beliefs.

Definitely agree, but the thing I worry about the most are the children of these parents. How many babies and young children have already been subjected to ‘faith healing’ and ended up dead? I’m not even counting those that haven’t been vaccinated because they believe vaccines are harmful to their children! I have heard of several cases of child deaths because parents believed in un-scientific nonsense and even prayer!! The god they prayed to must have been one incompetent bastard who has never given birth himself. The more this alternative ‘medicine’ or faith-healing is accepted, the more children will be at danger.

What adults do is their choice, and as long as I don’t have to pay for their useless potions, I can live with their choices. But when adults make choices for their children that endanger them, that’s a big worry and very scary indeed!

The point I am trying to make is that there is no difference between types of nonsense. There is just as much evidence for homoeopathy as there is for Catholicism, moon landing conspiracies, poltergeists, mind control and DEW… and that if one is to be ‘respected’, the others are to be respected as well.

By declaring mind-control believers psychotic and Mormons normal, we are knowingly and willingly sawing off the branch on which we sit. The criteria should be presence and solidity of the evidence, not the respectability. Respectability waxes and wanes with the zeitgeist, evidence does not.

Nobody in her/his right mind will disallow people private belief in whatever they want to believe in, we do not want a thought police, but ‘respecting’ certain beliefs and not-respecting others while not bringing credible criteria to the table can’t be healthy.

I remember Robert Winston looking at Lourdes and claiming that he ‘respects’ that, while saying that, as a Jew, he prefers the evidence. In so doing, I think he shows he is not a critical thinker. He is trying to have his cake and eat it too. There is just as little evidence for his Yahweh as there is for the miracle powers of Lourdes. Therefore, there should be no ‘respect’ for either one.

By making a distinction based on nothing but belief/personal preference, he encourages people to reject that which they don’t like, and accept that which they do like, and in so doing, he encourages uncritical postmodernist nonthinking, suggesting that reality is what the believer thinks it is, not what the evidence points to.

In the battle against foot gangrene, foot amputation –while not perfect– is astonishingly efficient. Homoeopathy is even more astonishingly inefficient and so are prayer and burnt offerings to the traditional middle-eastern deities/deity. By ‘respecting’ these deities, and ridiculing homoeopathy, we create confusion. Unnecessary confusion. My point is that privileging Judaism directly and negatively affects the credibility of our ridiculing of homoeopathy, because it shows that our evidence-based thinking is not evidence-based at all, but preference-based and hence, just as non-credible as any other prescientific non-reasoning.

We must follow the evidence where it leads and not stop doing so when – for purely cultural reasons – it leads to conclusions we don’t like or are afraid of. If evidence stops being evidence when we don’t like it, the nature of evidence becomes uncertain.

Wow. Brillant stuff here. Especially the solidity vs respectability part. Forms of theism fall out of flavor with time (zeus,althena,…) and to bring them back today would probably be met with ridicule and reject from most cultures. The evidence for both (modern theism vs historical theism) is still zero – it just so happens that one is culturally accepted (and even defended…religiously).

You are making really good points here, Bart.

The only thing I’d like to mention is that we still need to make a distinction between faith in gods and faith in alternative healing methods because the beliefs in gods (I refuse to use a capital G) are not testable. A god is not falsifiable, whereas the belief in a certain alternative medicine or healing method IS falsifiable.

Does the alternative healing method get better results than, for example, a placebo or orthodox medicine or not? This can be tested and recorded.

Gods can not be falsified because they are not detectable and a scientist cannot test things that cannot be detected.

Maybe the all the wonderful things that believers claim their god can do can be testable, such as heal the sick through prayer, but the thing is that it makes no difference to the believer whether a prayer gets answered or not. They will keep believing regardless, because even though the person they prayed for maybe worsened or even died, believers have learned to accept that their god must have had a reason for not answering prayers, or they even blame themselves for not believing hard enough.

But that assumes there are no downsides to being prayed for. The big Framlingham cardiac prayer study found no significant effects. But the effect closest to significance was that patients who knew they were being prayed for had higher morbidity than those who either did not know or were not actively being prayed for.

Remember prayer is often the last option. It’s what you do when all other options in medical science are gone. So to a patient being told they are being prayed for could assume they are more in the last chance saloon than they had thought hitherto and turn their faces to the wall as a result.

First do no harm and that includes even apparently benign interventions like prayer.

The point Bart is trying to make (and he is right) is that your can’t make a distinction between the two because quackery is quackery. It’s counter-productive to fight it on one front while allowing it on another.

While it’s true that one is falsifiable and the other is not, the practitioners and followers of quackery don’t care about falsification. They don’t even understand what it means!

If they are allowed to fill gaps in knowledge with statements such as “he (it) works in mysterious ways” then they will assert mystery into area’s where we already have knowledge.

There is a Dutch poem, published in De tuinen van Suzhou (1986) by Bert Schierbeek:

zegt Li:

een pond veren

vliegt niet als

er geen vogel in zit

My translation:

‘Li says:

A pound of feathers

does not fly

when there is no bird inside’

Can this serve as a poetical summary of your chart?

It’s worth pointing out that Sweden has a law that makes use of CAM on children under 10 and pregnant women illegal.

That’s fantastic to hear, Malleus! Good to see some normalcy around the world!

The Dutch Society against Quackery organised a symposium last year about quackery with children. One speaker was Mats Reimer, a paediatrician from Sweden, and his story is a little less reassuring than the statement here above by Malleus. CAM is prohibited in Sweden in children under the age of eight, but this only pertains to CAM-practitioners without a medical training! Doctors practicing CAM as for instance anthroposophical doctors are free tot practice their homeopathy and alike quack treatments. This also counts for chiropractioners, if that is correct English. And even in spite of these liberties there is a strong pressure from CAM-adherents (united in the movement ‘Hela Barn’) to make alternative treatments available for children. They were even supported by the UN-committee for Human Right!

We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

T. S. Eliot

Which is why the Chinese Government is spending billions researching herbal medicine. Countries like China, India, Russia (and even Germany) don’t quite share your jaundiced views on natural medicine. Still, with China, India, Russia, the “stans” and Iran forming a single trading block under the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation I feel the views of the medical establishment(or anybody) in the West will become irrelevant,anyway.

Let me interpret ‘herbal medicine’ here for you. Governments around the world are pouring money into finding pharmaceuticals from native plants, fungi, sponges etc. etc. That this includes some traditionally used herbs just means they are low hanging fruit.

Remember herbal remedies that work get their active ingredient identified, so the dose can be standardised (a bit problem with fresh or dried herbs or tinctures made from them) and later synthesised. Only loons drink willow bark tea which is incredibly bitter. An aspirin is much better, an NSAID better and kinder to your stomach.

What is left over in the process either becomes a nice salad or pot pourri.

Hi Dr. Lewis. Looking back at your post, I love the notion of “The University of Google”. I reckon this reality encapsulates so many of the seeming strengths and problems of our dilemmas in public life. The graphs and quadrants also illustrate key facets of debate and policy, helping discussion. Thanks.